The exhibition The Universe on Paper. The Art of Linda Karshan and its aftermath

Giulia Martina Weston

Hosted in the beautifully-proportioned venue of the Domus Comeliana in Pisa, the exhibition I had the pleasure to curate in October 2022 aimed to shed light on the path pursued by distinguished American artist Linda Karshan.

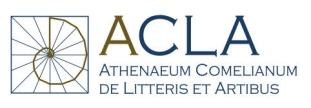

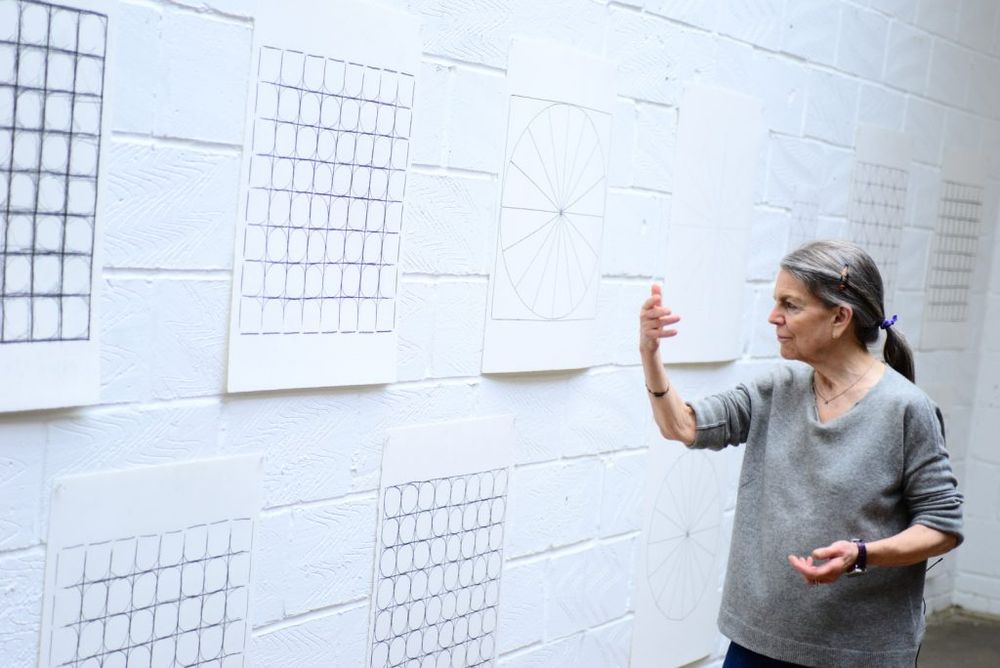

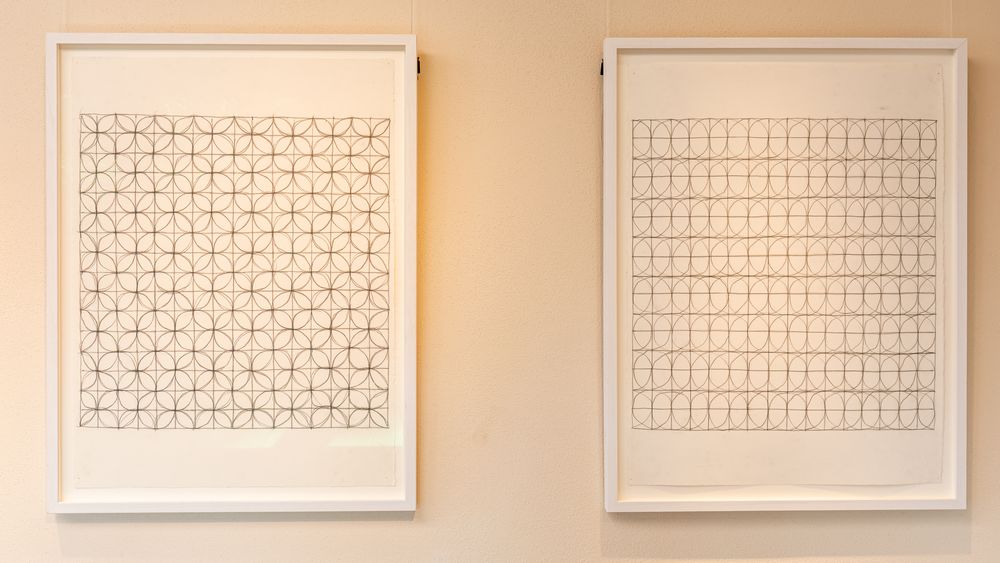

The show presented an exquisite selection of works on paper starting from a large work of 1983 and culminating in a suite of drawings of 2021, created during the Covid-19 pandemic. Collectively, they testify to the consistency of Karshan’s personal marks – particularly the constructive element of the grid, either manifest or implied – and the recurrence of seemingly geometrical patterns such as circles, squares or lozenges.

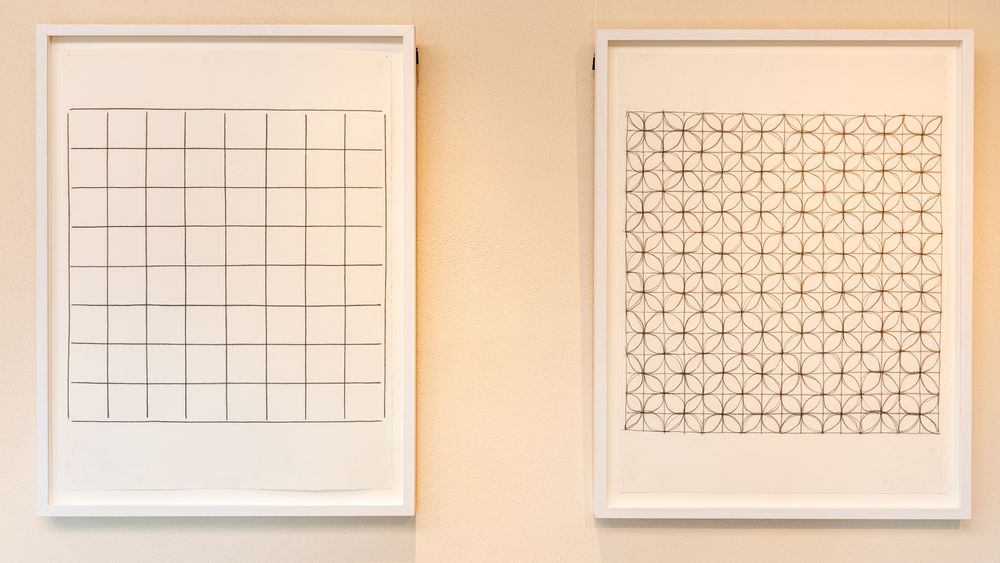

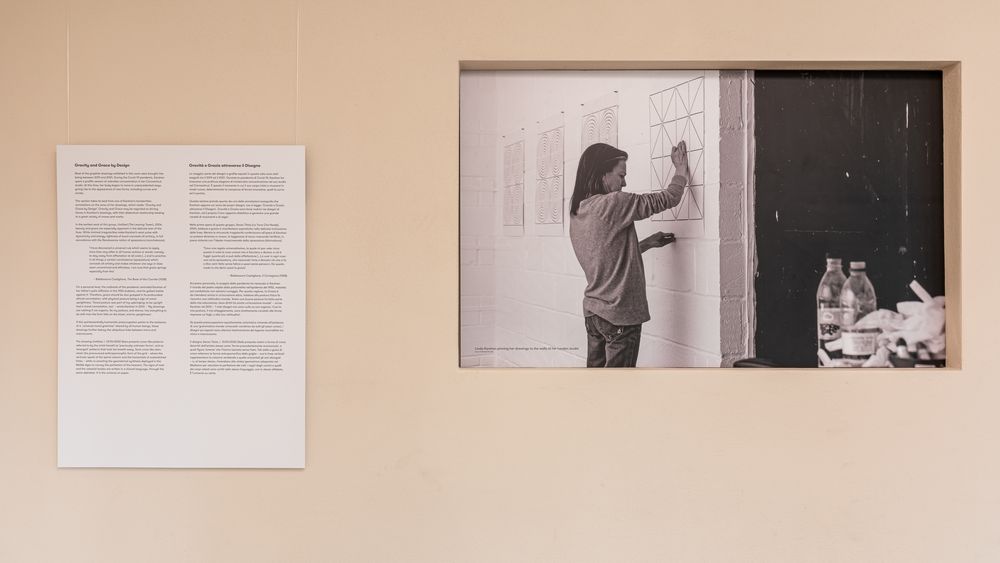

In 1994, Linda Karshan developed a performance-based method to bring her drawings into existence. Guided by what she termed her ‘inner choreography’, the artist draws freehand, standing at a table, and, despite being left-handed, uses her right. As she reaches forward with her graphite pencil, her left leg rises up naturally, so she balances like a ballerina in an arabesque and draws a line to a rhythm of 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8. She then goes back over it, and makes a 90-degree anticlockwise turn of the paper. Thus freed, or – better – found, Karshan’s iterative images of intersecting lines, geometrical shapes and organic patterns stem from her rhythmic breathing, her anticlockwise turn of the paper, and the motion of her entire body and mind.

Surprisingly, Karshan’s oeuvre naturally resonates with the humanistic aspiration pursued by Professor Marcello Comel (1902-1995), the founder of the Institutio Santoriana Fondazione Comel. Displayed in the prestigious venue of the Domus Comeliana in Pisa – in the first exhibition hosted by the Institutio Santoriana Fondazione Comel – Karshan’s works become a testament to contemporary humanism.

The Body and Mind: moti dell’animo

The display presented a suite of Karshan’s early works, across a range of formats and media, ranging from mixed media to the exclusive use of pen or pencil. In this remarkable variety, the artist’s modus operandi (working method) could be grasped at a glance, with marks becoming signs of the movements of the hand holding a stick of graphite or a pen against the resistance of the paper. These dynamic marks find their origin in the connection between the movements of the body and those of the mind, in accordance with what Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) termed moti dell’animo.

The earliest work, Untitled (the Deluge), is an abstraction of an arrangements of tools made in 1983. The dynamism of curved lines gives rise to a highly vigorous microcosm, in which the artist’s creative furor (energy) proportionally matches the unrestrained forces of the universe. As such, this drawing finds unexpected yet meaningful parallels in Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches of storms and deluges.

In between abstraction and figuration is the grid-like structure which gradually emerges in several works of the display, such as the jewel-like Untitled, 1994, an exercise in energetic scribbles and proportion drawn in pen on file paper. The grid, perceived by Karshan as ‘the figure assigned to me’, is an ancestral anthropomorphic form, in which the verticals speak of the spinal column and the horizontals of outstretched limbs.

Whether manifest (Untitled, 1996) or implied (Untitled, 1993), the grid ensures harmony and balance among the compositional forces and patterns. In this harmony lays a cornerstone of Renaissance humanistic thinking: the connection between the order of the universe (macrocosm) and that of men (microcosm), under the sign of proportion and the auspice of a shared alphabet.

Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe, which stands continually open to our gaze. But the book cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language and read the letters in which it is composed. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it; without these, one wanders about in a dark labyrinth

Galileo Galilei, The Essayer (1623)

Towards Perfection

Matching the quiet grandeur of the iconic staircase of the Domus Comeliana, the show presented the series of seven etchings titled NE 1-7 and carved in 2002. ‘NE’ stands for ‘North East’, an especially industrious and creative area of Karshan’s native Minneapolis, and the location of Todd Norsten’s print shop, where the artist has always felt at home.

As the gracious elegance of the lines makes clear, this reference to a virtuous civic space is more than just nominal. Collectively, the pieces formally recall Renaissance town plans, in which seemingly geometrical patterns are ultimately signs of men, with ethics and aesthetics overlapping.

Furthermore, this exquisite series corroborates the argument that Karshan’s works chiefly embody the literary values discussed by Italo Calvino in his Six Memos for the Next Millennium (published posthumously in 1988): lightness, quickness, exactitude, visibility, and multiplicity. Consistency would have been the sixth and last value; Karshan’s oeuvre is a stunning example of the consistency of ‘the moving figure assigned to her’, over time.

While Albers and LeWitt, my closest neighbours, are concerned to eliminate the human touch, my etchings are nothing if not human and humane – nothing if not figurative

Linda Karshan, 2017

Gravity and Grace by Design

Matching the quiet grandeur of the iconic staircase of the Domus Comeliana, the show presented the series of seven etchings titled NE 1-7 and carved in 2002. ‘NE’ stands for ‘North East’, an especially industrious and creative area of Karshan’s native Minneapolis, and the location of Todd Norsten’s print shop, where the artist has always felt at home.

Most of the graphite drawings exhibited in the Sala degli Ulivi on the first floor were brought into being between 2019 and 2021. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Karshan spent a prolific season of unbroken concentration in her Connecticut studio. At this time, her body begun to move in unprecedented ways, giving rise to the appearance of new forms, including curves and circles.

This section took its lead from one of Karshan’s handwritten annotations on the verso of her drawings, which reads: ‘Gravity and Grace by Design’. Gravity and Grace may be regarded as driving forces in Karshan’s drawings, with their dialectical relationship leading to a great variety of moves and marks.

In the earliest work of this group, Untitled (The Leaning Tower), 2004, beauty and grace are especially apparent in the delicate lean of the lines. While minimal irregularities make Karshan’s work pulse with dynamicity and energy, lightness of touch conceal all artistry, in full accordance with the Renaissance notion of sprezzatura (nonchalance).

I have discovered a universal rule which seems to apply more than any other in all human actions or words: namely, to stay away from affectation at all costs […] and to practice in all things a certain nonchalance (sprezzatura) which conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless. I am sure that grace springs especially from this

Baldassarre Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier (1528)

On a personal level, the outbreak of the pandemic reminded Karshan of her father’s polio affliction in the 1952 endemic, and his gallant battle against it. Therefore, grace should be also grasped in its profoundest ethical connotation, with physical posture being a sign of moral uprightness. ‘Good posture was part of my upbringing; to be upright had a moral connotation, too’ – wrote Karshan in 2013 – ‘My drawings are nothing if not organic. So my posture, and stance, has everything to do with how the form falls on the sheet, and its uprightness’.

If this quintessentially humanistic preoccupation points to the existence of a ‘universal moral grammar’ shared by all human beings, these drawings further betray the ubiquitous links between micro and macrocosms.

The drawing Untitled, I. 13/04/2020 Stars presents cross-like patterns referred to by the artist herself as ‘previously-unknown forms’, and as ‘emerged’ patterns that took her breath away. Such cross-like stars retain the pronounced anthropomorphic form of the grid – where the verticals speak of the spinal column and the horizontals of outstretched limbs – while re-enacting the geometrical synthesis deployed in the Middle Ages to convey the perfection of the heavens. The signs of men and the celestial bodies are written in a shared language, through the same alphabet. It is the universe on paper.

The Gift

The two photographs still exhibited in the entrance hall of the Domus Comeliana are titled The Orlo and The Orlo Reversed, and belong in the project Karshan Time carried out by photographer Tom Fecht between 2004 and 2009.

Fecht photographed Karshan at work in his Basel studio, complete with skylight. As night fell, she was obliged to draw with a torch in space, moving in obedience to the figure assigned to her. Needing to ‘draw in space’, Karshan had to turn; the ‘on-the-spot choreography’ came to her without missing a beat.

Intrigued by the performative nature of Karshan’s practice, and her choreographic language to mark out time in space, Fecht set out to capture the recurring patterns of Karshan’s movements, forward and backward – or upwards and downwards. In his photos, Fecht shows the artist as she enacts, and marks out, again and again, ‘the figure assigned to her’, making the invisible visible, and witnessing the subconscious aspects of Karshan’s long-established drawing rituals.

In 2005, Karshan recalls the first impressions of this prolific interaction with Fecht and the medium of photography by stating:

‘So upright and regular were my rotations round my centre, the resulting ovals of light, called the orlo, recall Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man – complete with ghosted arms moving within’.

While the term orlo (contour) finds its source in Leon Battista Alberti’s Treatise on Painting (1435), the empirical and geometrical interplay between the order of the universe (macrocosm) and that of men (microcosm) has its most renowned precedent in Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1490, Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia).

That Leonardo has been a constant point of reference in Karshan’s artistic practice and scholarly research is confirmed by several passages of her studio jottings:

Leonardo was looking for vital form, an analogy. He was constantly searching for a universal system of proportion that would explain the fundamental workings of forces. Further, he was the first to tie the artist’s notion of proportional beauty into the wider setting of proportional action of all the powers in nature.

Proportional action is at the core of my being; it determines all that I do. From my mind, where I experience proportion as numbers and rhythms, through my body onto the sheet, proportional beauty gets marked out. In this way I show that man can be measured, and that my measure is my reach as performed in real time

Linda Karshan, 2006

The Orlo and The Orlo Reversed were donated by Linda Karshan to the Institutio Santoriana Fondazione Comel to mark the first exhibition in the history of the Institution. Humanistic in spirit, this gift represents a significant addition to the collection of 20th-century paintings assembled by professor and philanthropist Marcello Comel (1902-1995). The permanence in Pisa of The Orlo and The Orlo Reversed is meant to inspire the present and future generations of scholars and art lovers.

At the time of the show, Linda Karshan and I could not have anticipated what was to come next. In 2023, the Atheneaum Comelianum de Litteris et Artibus was established to fulfill Comel’s humanistic dream, and we were nominated President and Director respectively. Looking forward, I feel honoured to be part of this exciting new chapter in the history of the Institutio Santoriana Fondazione Comel. In keeping with Comel’s vision, and with Karshan’s contemporary humanism, the story unfolds in pursuit of the true, the good, and the beautiful.